Student support services and the third space: Spanning the boundaries of learning ecologies

In the context of widening participation in higher education, the roles of those who work in the third space to support an increasingly diverse student cohort are crucial, yet their importance is often underestimated and/or misunderstood. This is partly because the roles themselves are highly diverse, and span the continuum between academic and administrative student support at one end and academic development of teaching staff at the other. Both have a large potential impact on student success, as do all the relevant third space roles in-between, including for example students as partners, student guild members, those assisting with residential colleges, counsellors, and the list goes on. In fact, in a newly released volume, simply called Student Support Services (Huijser et al., 2022), the extent of the diversity of the roles becomes very clear across almost 50 chapters and more than 900 pages!

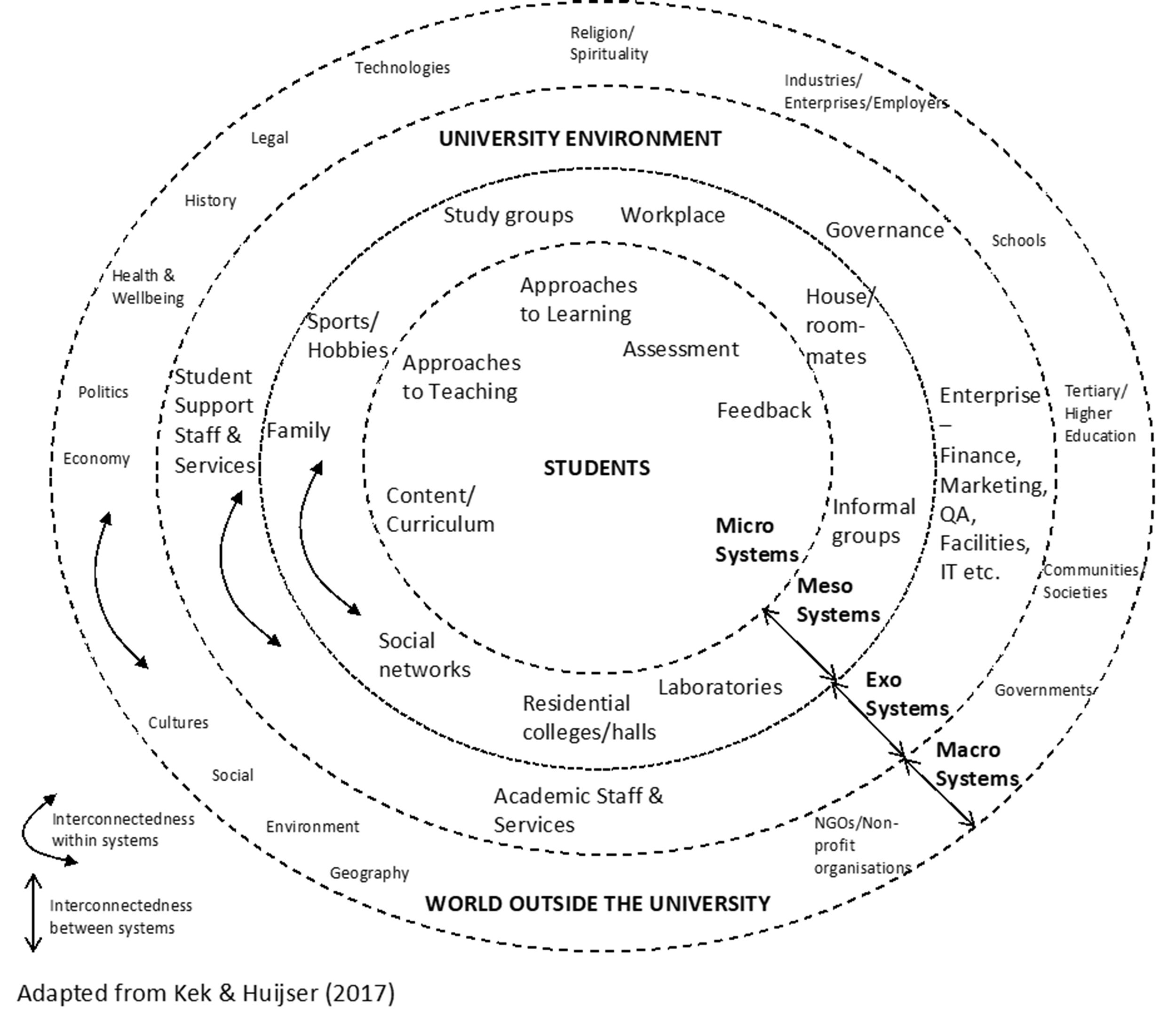

Drawing on Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecology of human development, which is based on interacting bio-eco-systems, the concept of a learning ecology consists of four different systems: microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem. Each of these systems relate to a different dimension of the learning environment. For example, the microsystem exists within the university and includes the curriculum, assessment, teaching approaches, and so on; by contrast, the macrosystem refers to national economies, governments, and so on. The boundaries between these systems are porous, and each system impacts on the others. Like a biological ecology, a change in one system impacts not only on that particular system, but on the ecology as a whole. The key point to make here is that the university is only a part of this ecology, and that there are many other factors that impact on the learner (see illustration)

Thus, the notion of learning ecologies is useful, as it can show us the complexity of what is involved in a successful student learning experience, and indeed even what we mean by a successful learning experience. Learning doesn’t just happen in formal learning environments and not only do students come to university with diverse prior knowledges, but they also draw on many informal learning experiences which they access via the media, family and friends, and a range of other avenues. All of this learning is connected and crosses boundaries in a learning ecology, and given that ecologies are by definition fragile, it is important that universities recognise and value the roles of those in the third space who can have an impact on the various elements of such a learning ecology, and can thus have a big potential influence on student learning experiences.

Geoff Scott, in his contribution to the book, questions the purpose of universities, and he makes an important distinction between what he calls ‘fit for purpose’ and ‘fit of purpose’, which goes to the heart of that question, and which is a challenge taken up by many others in the book. In other words, what are universities actually trying to achieve? If the goal is simply to help graduates find a job, and to satisfy students as customers, then as soon as a high percentage of them do find a job (and of course this can be measured) then fit for purpose is being achieved. However, Scott, like many others in the book, argues that we should be a lot more ambitious at a time when we face a range of wicked problems on a global scale, such as climate change and pandemics. Therefore, we should redefine the ‘fit of purpose’ of universities to include their role in addressing such problems.

For that, we need to see and develop students as learners. Of course, this is not a simple binary, and indeed some argue that the two can co-exist, and indeed do. Again, the notion of a learning ecology is useful here, because it can capture the complexity of not only how students learn, but it also allows us to map out what (and importantly who) contributes to this learning, and how. This includes the possibility of mapping third space roles within a learning ecology, which is in many ways is what the Student Support Services volume has done.

What has become clear in exploring these learning ecologies is the sheer breadth and depth of the impact that third space workers have on student learning and the overall student experience in the higher education sector right across the globe. Recognising this is important, not only because the people who perform these roles deserve recognition and respect, but also because it allows us to improve what we do with the right levels of support. Ultimately, this can only benefit students and by extension the rest of us.

Huijser, H., Kek, M. Y. C. A., and Padró, F. F. (2022) (editors) Student Support Services, Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5852-5

Kek, M. Y. C. A. and Huijser, H. (2017). Problem-based learning into the future: Imagining an agile PBL ecology for learning. Singapore: Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-10-2454-2